Ogura Hyakunin Isshu

#1. 天智天皇 Emperor Tenji (626-672) was the 38th Emperor of Japan. After overthrowing the Soga clan, he implemented the Taika reforms, moved the capital to Omi (Shiga Prefecture), and reigned as one who sincerely cared about his people, sympathizing, as here, with the peasants.

| 秋の田の | In the autumn rice field |

| かりほの庵の | temporary harvest hut, |

| 苫をあらみ | because of the loose rush-mat roof, |

| わが衣手は | my sleeves are |

| 露に濡れつつ | becoming wet from the dew. |

【秋の田の】 autumnal rice field.

【かりほの庵の】 かりほ is a kake-kotoba meaning ‘harvested grain’ (刈穂) and ‘harvest hut’ (仮庵); かりほ のいほの also enhances the rhythm by repeating the two syllables (hono).

【苫をあらみ】 とま ‘sedge mat’ あ らい ‘rough, loose.’ Noun を Adj み gives the reason. Elision: tomawarami

【わが衣出は】 が indicates possession; ころもで is a ka-go meaning ‘sleeves.’

【つゆにぬれつつ】 [(ぬる wet 下用)(つつ Continuative)] ‘keeps getting wet’ from the dew dripping through the roof.

Commentary: This poem alludes to an occasion on which the Emperor was helping farmers by scaring away birds as they harvested the crop. In a sudden rain shower, he sought shelter in a make-shift hut, thatched only with coarse rushes which afforded little protection. The slow, quiet dripping of the dew from the roof contrasts with the sweat of the farmers harvesting the rice. Mindful of their difficult labor, the Emperor sympathizes with the peasants.

#2. 持統天皇 Emperor Jitō (645-702), daughter of Emperor Tenji and 41st Emperor of Japan, ruled after her husband, the Emperor Tenmu, had died. At that time, smooth transition in the seasons was attributed to the wise rule of the Emperor. So, the depiction of summer arriving after spring has passed conveys a sense of hopefulness and satisfaction with the reign.

| 春過ぎて | Springtime having passed, |

| 夏来にけらし | summer seems to have arrived. |

| 白妙の | The snow-white |

| 衣干すてふ | robes are being dried, they say, |

| 天の香具山 | on celestial Kaguyama. |

【春過ぎて】 [(すぐ pass 上用)( つ Perfect 下用)]

【夏来にけらし】 [(く come カ 用)(ぬ Perfect ナ用)(けらし=け るらし Past Conjecture)]

【白妙の】 白妙 is a makura-kotoba for white objects such as snow.

【衣干すてふ】 (ほす dry サ終); てふ = といふ ‘they say’ since the practice had been discontinued. (い ふ say 四終)

【天の香具山】 Legend has it that Kaguyama descended from the sky, hence the 天の in front of 香具山; taigen-dome.

Commentary:

The white robes, a symbol of freshness and invigorating spirit, are the vestments of the shrine that priestesses used during summer Shinto rituals. Moreover, the sincerity of one’s behavior is said to be revealed by wetting clothes with holy water then drying them. The hill lies southeast of Nara and could be seen from Emperor Jito’s palace. This poem alludes (honka-dori) to one in Manyoshu, varying only with きにけらし for きたるらし and ほすて ふ for ほしたり.

The poets of #1 and #2 (Emperors Tenji and Jitō) and of #99 and #100 (Emperors Gotoba and Juntoku) bear a parent-child relationship. #1 conveys Tenji’s sympathy with the hardships of the peasants, and #2 depicts Jito’s wise reign, while #99 and #100 have darker tones and meanings, giving an interesting contrast between the beginning and end of Hyakunin Isshu.

#3. 柿本人麿 Kakinomoto-no-Hitomaro (662-710), an orphan found at the base of a persimmon (柿) tree, was a court poet under Emperor Jitō and one of Japan’s four greatest poets along with Teika (redactor of HNIS), Sogi, and Basho. Many of his poems were based on his mourning for his wife.

| あしびきの | The lofty |

| 山鳥の尾の | mountain pheasant’s tail – |

| しだり尾の | (like a) drooping tail, |

| ながながし夜を | this long, drawn out night |

| ひとりかも寝む | must I sleep alone? |

【あしびきの】 Makura-kotoba for mountains, skillfully introduced into the mountain pheasant’s name.

【山鳥の尾の】 山鳥 pheasants

【しだり尾の】 (しだる droop ラ体); の = のような (like, as). The tail is a jo-kotoba for ながながし below.

【ながながし夜を】 ながし kake-kotoba ‘long’ (長) and ‘drift’ (流); よ kake-kotoba ‘night’(夜) and ‘life’(世); (ながながし very long シ ク体 [古い語法]/終)

【ひとりかも寝む】 か shows uncertainty and forms a kakari-musubi with ねむ;も emphasis. ねむ kake-kotoba 'enjoy together’(合歓) and ‘sleep’ [(ぬ sleep 下未) (む Speculation 四体)]

Commentary: This poem depicts a lonely night separated from one’s lover. The male copper pheasant, known for its long tail, was believed to part from its mate at night. The term “山鳥” calls to mind the plight of sleeping by oneself. The jo-kotoba describes a copper pheasant’s droopy, long tail and repeats the particle の four times to help the reader visualize the deep, lonely night. The lengthy jo-kotoba also symbolizes this loneliness. Line 4: ‘long night’ or ‘drifting life’ and the next phrase convey the writer’s emotion by asking, “must I sleep alone through this long, drawn out night?” It is here that the poet expresses sorrow at spending the night alone. This phrase alone would have been enough for the purpose of a love poem, but the visual image of the copper pheasant’s long, droopy tail elicits the reader’s emotion and sympathy even more strongly.

#4. 山部赤人 Yamabe-no-Akahito (700-736), was a Nara court poet who composed many of his works during journeys with Emperor Shōmu.

| 田子の浦に | On Tago Bay |

| うち出でてみれば | going out to take a look |

| 白妙の | on pure-white |

| 富士の高嶺に | Fuji’s high peak |

| 雪は降りつつ | snow keeps falling. |

【田子の浦に】 Tago Bay in Kampara, Shizuoka City.

【うち出でてみれば】 [(出づ emerge 下用) (つ Perfect 下用)] [(見 る see 上一已) (ば Resultative)] “when I go out to look.” Elision: uchidetemireba.

【白妙の】 白妙 is a makura-kotoba for white objects such as clouds and snow.

【富士の高嶺に】 “On Mount Fuji’s high peak”

【雪は降りつつ】 [(降る fall 四用) (つつ Continuation)]

Commentary:

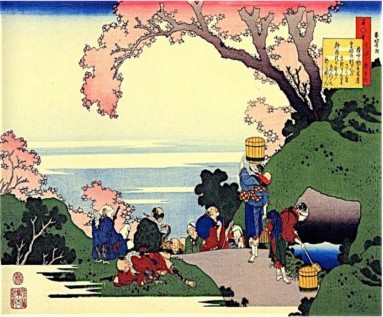

This poem portrays a scenic outlook and depicts the wonderful moment when obstructions evaporate and one’s view suddenly opens up to the ocean and Mount Fuji. Its expanse contrasts the blue sky and ocean with Fuji’s perfectly white lofty peak.

Yamabe’s original in Manyoshu Volume 3:318 is a han-ka (田子の浦ゆうち出 でてみれば真白にぞ不尽の高嶺に雪は降りける). Both the chō-ka (long poem) and the han-ka suggest that the white snow on Mount Fuji is not just a beautiful scene, but also a symbol of divine sublimity (kami). In the past, Mount Fuji was worshiped as a nature god before whom humans were compelled to bow down in reverence.

#5. 猿丸大夫 Sarumaru Daifu (fl. 705-718?) was a Heian waka poet, if there actually was such a person.

| 奥山に | In the secluded mountains |

| 紅葉踏み分け | treading through the autumn leaves |

| 鳴く鹿の | the call of a stag – |

| 声聞く時ぞ | when I hear its voice |

| 秋は悲しき | autumn is sad. |

【奥山に】 おく ‘secluded’

【紅葉踏み分け】 There is some ambiguity over whether a person or a deer is treading through the leaves. [(ふむ tread 四用) (わく divide 下用)]

【鳴く鹿の】 In the autumn, a stag usually gives out a mating call, which implies a yearning for a wife or lover. (鳴く cry 四体)

【声聞く時ぞ】 ぞ emphasizes ‘sad’ and forms a kakari-musubi with か なしき below. (聞く hear 四体)

【秋は悲しき】 は distinguishes its subject from other less significant subjects. Here it means ‘more than other seasons, autumn feels sad.’ (悲 しき sad シク体)

Commentary: This poem portrays a beautiful scene, in which a lonely stag, as he treads through the colorful, fallen autumn leaves, calls for his mate. As the poet, also presumably walking through the autumn leaves, hears the cry, he is overwhelmed with sadness. In Chinese poetry, “秋悲 (autumnal melancholy)” derives sadness from seeing withering plants in the autumn. Japanese poets also depict autumn as a melancholy time of the year, while farmers see autumn as the busy harvest season preceding the idleness of the long winter. Beyond the loneliness, there is also a sublime serenity, the peace of mind that many find in aloneness. For aristocrats unable to enter the priesthood or to live in the secluded mountains, waka served as a means to experience life as an ascetic.

#6. 中納言家持 Chūnagon Yakamochi (718-785), was a Nara poet of the warrior-bureaucrat Otomo clan. Chūnagon is a high bureaucratic position. He is said to have been one of the final editors of Manyoshu.

| 鵲の | On Magpie |

| 渡せる橋に | Crossing Bridge |

| 置く霜の | gathered frost – |

| 白きを見れば | when I see how white |

| 夜ぞ更けにける | I feel the night is slipping away. |

【鵲の】 Magpies are a symbol of happiness in China. The magpies join their wings to form a bridge.

【渡せる橋に】 The Milky Way. は し is a kake-kotoba: bridge (橋) and stairway (階) [(渡す cross 下未) (る Potential ラ体)]

【置く霜の】 Frost forms just before day break. It is a metaphor (mitate) for the cold shining stars in the winter night sky. (置く place 四体)

【白きを見れば】 [(見る see 上一已) (ば Resultative)]

【夜ぞ更けにける】 ぞ is for emphasis and forms a kakari-musubi with ふけにける. [(更く pass 下 用) (ぬ Past ナ用) (ける Exclamation ラ体)]

Commentary: Stars in the winter transforming into hoar frost – what a magical moment! This poet uses just 31 syllables to describe a magnificent winter wonderland in the sky, while he laments that the night has almost passed. In Chinese legend, the Weaver (Vega) is only permitted to meet her husband the Herdboy (Altair) on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month on a bridge formed by flights of magpies that take pity on them. Magpie Bridge is a metaphor (mitate) for the stairway to the Imperial Palace in Kyoto. The Imperial Court is also often compared to the celestial world. Guarding the Palace late at night and seeing the frost-covered stairway, the poet thinks to himself that the night is passing, and maybe it is just like that on the bridge in the sky.

#7. 安部仲麿 Abe-no-Nakamaro (701-770), was a waka poet, administrator, and scholar in the Nara period. At 16, he went to China, where he passed the civil-service examination and took the position of a Governor- General. He tried to return to Japan but a shipwreck forced him to stay in China for the remainder of his life.

| 天の原 | The expanse of sky – |

| ふりさけ見れば | being far off, I see |

| 春日なる | in Kasuga |

| 三笠の山に | over Mount Mikasa, |

| 出でし月かも | the rising moon! |

【天の原】 はら ‘wide plain’

【ふりさけ見れば】 “as I look into the distance.” (ふりさく act from afar 下用) [(みる see 上―已) (ば Resultative)]

【春日なる】 Kasuga Shrine in Nara was where the envoys prayed for a safe journey. (なる be at/in ナリ体)

【三笠の山に】 Mount Mikasa in Nara.

【出でし月かも】 か adds emphasis and forms a kakari-musubi with いでし. The poet is comparing the moon that he then sees in China with the moon that he watched rise over Mount Mikasa in Japan. [(出づ emerge 下用) (き Past 体)]

Commentary: The poem was written at a farewell banquet for Nakamaro in Mingzhou (present-day Ningbo, China) before he set off for Japan. Seeing the majestic moon rising in the sky, the poet was reminded of the same moon that rose over Mount Mikasa where he had prayed for a safe journey before he left Japan. After three decades, it was finally time to return to his mother country. Feeling nostalgic, Nakamaro composed this poem. The great Chinese poet Li Bai’s famous verse, “ 頭を挙げて山月を望み 頭を低れて故郷を思う” (“Raising my head, I gaze at the bright moon; lowering my head, I think of home.”) also captures this nostalgia.

#8. 喜撰法師 Kisen Bonze (9th century), a poet and Buddhist monk, was said to have lived on Mount Uji, (宇治) a homonym for sorrow (憂).

| わが庵は | My hut |

| 都の辰巳 | southeast of the capital |

| しかぞ住む | so I inhabit |

| 世をうぢ山と | this place, the Mount of Sorrow, |

| 人はいふなり | or so people call it. |

【わが庵は】 庵 is a humble reference to the poet’s home.

【都の辰巳】 都 refers to Kyoto. Southeast was located in between 辰 (たつ - ESE) and 巳(み - SSE).

【しかぞ住む】 しか ‘thus,’ not a deer (鹿). ぞ adds emphasis and forms a kakari-musubi with すむ. (住む live 四体)

【世をうぢ山と】 世 ‘world,’ ‘place’; うぢ is a kake-kotoba meaning a place (宇治) in Kyoto and ‘gloomy’ (憂). 山と is a kake-kotoba meaning “mountain” and Yamato, the ancient name for Japan (大和).

【人はいふなり】 なり implies hearsay. [(いふ say 四体) (なり be ラ終)]

Commentary: Legend has it that Kisen Bonze was in actuality a mountain wizard who made an elixir of immortality. Such stories add an aura of mystery to this poem as the reader tries to understand Kisen’s life in the mountains. Although people thought that Kisen lived a secluded life on the Mount of Sorrow because he couldn’t bear the hardship and sorrow of the outside world, Kisen was not only content with his tranquil and peaceful life, but also grateful for the worldly concern people had for him. This poem does not convey the loneliness of a recluse, but rather the contentment of a free and unrestrained life. Its ending sets a light and cheerful mood, with an image of Bonze Kisen unconcerned with worldly matters.

#9. 小野小町 Ono-no-Komachi (825-900), a famous waka poet, the adopted daughter of Ono-no-Takamura (#11) and renowned as a rare beauty, she specialized in complex erotic love poems. She is said to have ended a drought in 866 by her magical powers.

| 花の色は | The flower’s color |

| うつりにけりな | has sadly faded |

| いたづらに | pointlessly – |

| 我が身世にふる | so has my beauty faded away |

| ながめせしまに | as the long rain pours down. |

【花の色は】 はな refers not only to flowers, but also beauty and youth.

【うつりにけりな】 [(うつる wither 四用) (に Past ナ用) (けり Past ラ 終)] な – Exclamation

【いたづらに】 ‘in vain’

【我が身世にふる】 世 kake-kotoba meaning ‘world’ and ‘relationships’; ふる also a kake-kotoba:‘fall’ (降) and ‘old’ (古).

【ながめせし間に】 ながめ kake-kotoba: ‘long rain’ (長雨) and ‘gaze at’ (眺). Hence, ‘while the rain falls on the world’ or ‘while lost in thought, my life passed by.’ (ながむ gaze at 下未) (す Causative 特用) (き Past 特終)

Commentary: This poem captures a beautiful woman’s lament over her withered beauty. The kake-kotobas intertwine tangible scenes with intangible feelings. The poet could be gazing long (ながめ) at the wilted flowers (花の色), while the spring long rain (ながめ) continues to fall (ふる) into the world (世), or the same set of words could refer to her lost beauty and sensuality (色) and her aged (ふる, 世) self, while she has been lost in her idle thoughts (ながめ, い たづらに), as if time has played a prank (いたづらに) on her. The similarity between raindrops/teardrops and the feeling of entrapment induced by the long rain relates rain to the sorrows of aging.

#10. 蝉丸 Semimaru (fl. 920) was either the son of Emperor Uda or servant of that Emperor’s eighth son. Legend also depicts him as a blind master of the biwa (a musical instrument), amusing himself in a hut in the hills near the Osaka Gate, on the edge of Lake Biwa.

| これやこの | This indeed is where – |

| 行くも帰るも | leaving and returning, |

| 別れては | or having parted |

| 知るも知らぬも | with known and unknown people |

| 逢坂の関 | they meet – this Osaka Gate |

【これやこの】 や adds exclamation.

【ゆくもかへるも】 People leave and return to Kyoto through this gate. (行く go 四体) (帰る return 四体)

【別れては】 わかれ, to part, contrasts with あふ to meet. [(別る part 下用) (つ Perfect 下用)].

【知るも知らぬも】 (知る know 四体) [(知る know 四未) (ず Negative 特体)]

【逢坂の関】 あふさか is a kake-kotoba meaning ‘meet’ and ‘Osaka.’ The gate was a well-known checkpoint as an important trade pass to and from the capital, Kyoto. taigen-dome.

Commentary: This poem depicts the vicissitudes of life as departure, encounter, and reunion are constantly happening at Osaka Gate. Three sets of phrases, 行く and 帰る, 知る and 知らぬ, 別れ and 逢ふ, form antitheses that describe the Osaka checkpoint. This poem reflects the Buddhist concept of 無常 (むじょう- ‘inconstancy’), the transient nature and evanescence of life and the idea that we meet only to part. It is as if one were looking down at a busy intersection in a city from a nearby building’s rooftop and saw the hustle and bustle of the world as people constantly pass each other by. Yet there is also a sense of serenity as one looks down at such scene as if it were a miniature of life of which the narrator is not part.

#11. 参議篁 Councillor Takamura (802-853), poet and scholar, was appointed assistant envoy to China in 834, but quarreled with the chief envoy and so was banished to the Oki Islands (Sea of Japan). Within two years, though, he returned to the capital and was promoted to the position of Councillor.

| わたの原 | That ‘Over the wide sea |

| 八十島 | crossing over to the eighty isles |

| 漕 |

we have set off rowing,’ |

| 人 |

please notify (my) people, |

| 海人 |

o mariner’s fishing boat. |

【わたの原】 The ocean’s (海 – wata) plain (原 – hara).

【八十島かけて】 80 = ‘many’ [(か く aim at 下用)(つ Perfect 下用)]

【漕ぎ出でぬと】 The first three lines are the content of 告げ. Elision – ‘kogide’ [(こぐ row 四用) (いづ emerge 下用) (ぬ Perfect ナ終)]

【人には告げよ】 人 refers to family and friends in Kyoto. 告げ conveys an imperative tone for a request. よ is an interjectory particle. (つぐ notify 四命)

【海人の釣り舟】 海人 means “seaman” and 釣り舟 is “fishing boat.” The poet addresses his request to the fishing boat. (つる fish 四用), taigen-dome

Commentary: This poem was composed as the poet was setting sail for the Oki Islands during his banishment. Shortly before departure for China as an assistant envoy, the author discovered that the chief envoy Fujiwara-no-Tsunetsugu had replaced his own damaged ship with that of the author, whereupon the author wrote a satirical poem called “Saidō no Uta,” which irritated Emperor Saga, who exiled him to Oki Province. Before departing, Takamura requests a nearby fishing boat to announce his departure. This poem gives the impression not only of subtle desperation, but also of quiet dignity. Without knowing the background of this poem, one might think that the poem depicts a courageous sailor ready to set off on a great adventure.

#12.

僧正遍照

| 天 |

Ye winds of heaven, |

| 雲 |

that pathway of the clouds, |

| 吹 |

please blow it closed. |

| 乙女 |

The maidens’ figures |

| しばしとどめむ |

might then tarry awhile. |

【天つ風】 つ = の

【雲の通ひ路】 The path to heaven from earth, whereby celestials ascend. (かよふ go through 四用)

【吹き閉ぢよ】 Blown closed so that the celestial maidens will stay. [(ふく blow 四用) (とづ close 上命)]

【乙女の姿】 乙女 “young ladies,” here refers to celestial maidens performing the Gosechi-no-Mai dance at the rice harvest festival.

【しばしとどめむ】 しばし “a short while.” む expresses the poet’s wish that they not go back to heaven quite yet. [(とどむ stay 下未) (む Conjecture 四終)]

Commentary:

Written before Henjō became a priest, this poem compares the five dancing maidens to celestial maidens. 雲の通ひ路 is the path by which the young maidens exit the room or stage, here compared to the path by which celestial maidens ascend to heaven. He is afraid they will fly back to Heaven and so requests the clouds to block their way, a fantasy that was probably shared by other witnesses to the dance as well.

The metaphor of the dancers as celestial maidens is said to have originated when Emperor Tenmu composed the following poem, supposedly as he was playing on a zither and the celestial maidens descended while dancing: 乙女ども 乙女さびすも 唐玉を袂にまきて 乙女さびすも.

#13.

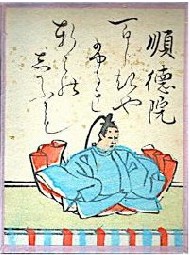

陽成院

| 筑波嶺 |

The peak of Mount Tsukuba, |

| 峰 |

falling from the mountaintop |

| みなの |

the Mina River - |

| 恋 |

the growing love |

| 淵 |

has become a deep pool. |

【筑波嶺の】 Tsukuba (Ibaraki) was believed to bestow marital harmony and bliss. During the Utagaki harvest rite, villagers sing and dance on their way up to the mountain peaks and often engage in free sexual activity. つく is a kake-kotoba meaning the place and accompany (付).

【峰より落つる】 (落つ fall 上体)

【みなの川】 The first three lines form the jo-kotoba for ふち.

【恋ぞつもりて】 こひ kake-kotoba “love” and “deep” (濃). ぞ forms a kakari-musubi with ぬる. [(つもる gather 四用) (つ Perfect 下用)]

【淵となりぬる】 淵 ‘deep pool’ [(なり become ラ用) (ぬ Perfect ナ 体)]

Commentary: Written for the third daughter of Emperor Kōkō, Imperial Princess Suishi, this poem expresses how Yōzei’s love towards Suishi has grown gradually into a deep passion, just as drops of water from the mountaintop collect to form streams, and eventually grow into rivers. The poem plays with the double meanings of sounds and words to combine the objective depiction of a natural scene with subjective personal emotions. Since Yōzei married Suishi afterwards, one might think that this love poem had a happy ending. However, for those familiar with Yōzei’s life, this poem, especially the mention of a “deep pool,” also conveys a sense of dark and deep-seated resentment. For physically assaulting his courtiers and violating taboos, Emperor Yōzei was deposed and lived 60 years as a reclusive Retired Emperor.

#14.

河原左大臣

| 陸奥 |

(Like) Michinoku’s |

| しのぶもぢずり |

Shinobu mojizuri - |

| 誰 |

on whose account |

| 乱 |

is this entanglement? |

| 我 |

It is not on mine! |

【陸奥の】 The northeast of Japan.

【しのぶもぢずり】 Mojizuri is a kind of cloth with a tangled pattern. しのぶ here is a kake-kotoba meaning the place, the material, and also ‘to endure/conceal,’ implying a secret love. Lines 1 and 2 are the jo-kotoba for 乱れ in the 4th line.

【誰ゆゑに】 “Who is the cause?”

【乱れそめにし】 そめ is a kake-kotoba meaning ‘begin’ (初め) and ‘dye’ (染め). 乱れ and そめ are the en-gos for もぢずり. [(乱る tangle 下用) (そむ dye/begin 下用) (ぬ Perfect ナ用) (き Past 特体)]

【我ならなくに】 に implies objection = ‘it’s your fault!’[(なる be ナリ未) (なく Negative)]

Commentary: Associating the exotic image of the Michinoku print from the Tōhoku region with one’s emotional confusion, this poem depicts a man’s secret love skillfully, using the metaphor in the jo-kotoba and the double meanings of the kake-kotoba. This poem is cited in the first paragraph of The Tales of Ise to express the tangled love of a man having just celebrated his coming of age towards the young beautiful sisters of Kasuga: 春日野の若紫のすり衣しのぶの乱れ限り知られず ‘Lovely as the new purple flowers of Kasugano, you have imposed on me this boundlessly entangled heart that is just like the pattern on the Shinobu-zuri.’

#15.

光孝天皇

| 君 |

For your sake |

| 春 |

going out to the spring fields |

| 若菜摘 |

I pick the young herbs; |

| わが |

on my sleeves |

| 雪 |

snow keeps falling. |

【君がため】 君 – you; が = の.

【春の野に出でて】 Elision: ‘harunononidete’ [(いづ emerge 下用) (づ Perfect 下用)]

【若菜摘む】 On the Festival of Seven Herbs on January 7, it is a custom to eat seven-herbs rice porridge, which is believed to bring longevity and health by expelling evil spirits. (つ む pick 四終)

【わが衣出に】 衣出 a ka-go for sleeves.

【雪は降りつつ】 Early spring snow, often regarded as a sign of good fortune in ancient Japan. [(降る fall 四用) (つつ Continuity)]

Commentary:

As written in the foreword of this poem in Kokin Wakashū, this poem was composed when Emperor Kōkō, still an imperial prince at the time, gave the green herbs to someone unknown. The receiver could be a lover, a courtier, or an ailing relative. Like Emperor Tenji whose sleeves become wet from the dew in a harvest hut in #1, the Imperial Prince went out to the fields in the snow as to pick herbs in the image of a sympathetic and ideal leader.

This poem portrays a beautiful scene by including the mellow images of the ‘spring fields,’ ‘young herbs,’ ‘sleeves,’ and ‘snow,’ and by contrasting the white of the snow with the green of the herbs. Such depictions of the colorful scenery and young herbs imbue liveliness – just what one needs when one has fallen ill. This also reflects the genuine and caring heart of the Emperor, as this will prove helpful in his future reign.

#16.

中納言行平

| 立 |

Having left, |

| いなばの |

I go to Mount Inaba’s |

| 峰 |

peak-grown |

| まつとし |

pines, if I hear (of your waiting), |

| 今帰 |

I will soon return. |

【立ち別れ】 having left. [(たつ stand 四用) (わかる leave 下用)]

【いなばの山の】 いなば is a kake-kotoba meaning the place (Tottori Pref.) and ‘if I go’ (往なば) [(いぬ go ナ未) (ば “if”)] Lines 2 and 3 are the jo-kotoba for まつ.

【峰に生ふる】 Elision – nyo (おふる grow 上体)

【まつとし聞かば】 まつ is a kake-kotoba meaning ‘pines’ (松) and ‘wait’ (待). し gives emphasis and means ‘poem’ (詩) and ‘death’ (死), while とし also means ‘year’ (年). (まつ wait 四終) [(きく hear 四未) (ば “if”)]

【今帰り来む】 [(かへる return 四 用) (く come カ未)]

Commentary:

Yukihira was departing Kyoto for his position as Governor in Inaba. The poem expresses his strong will to return, thus merging the dynamic aspects of life with the sadness of leaving.

The location and time implied in this poem include both the present (departing from Kyoto for Inaba) and the future (in Inaba longing to return to Kyoto). The poet has concisely expressed not only his unease at the upcoming departure, but also a hopeful anticipation of a future return. On a side note, this poem is often cited when one wishes for a parted friend or a lost pet to return.

#17.

在原業平朝臣

| 千早 |

Even in the majestic |

| 神代 |

age of the gods one never heard of |

| 龍田川 |

the Tatsuta River (turning) |

| からくれなゐに |

to brilliant crimson |

| 水 |

tie-dying the water. |

【千早ぶる】 Makura-kotoba for 神, suggesting the majesty and potency of the gods. ‘Even’ is implied by も in the next line. (ふる shake 四体)

【神代も聞かず】 The phrase implies something astonishing. [(きく hear 四未) (ず Negative 特用)]

【龍田川】 A popular spot in Ikoma (Nara) to view autumn maple leaves.

【からくれなゐに】 から indicates vibrant and elegant color. に indicates a transition or change.

【水くくるとは】 Tie-dyed water caused by the crimson maple leaves on the bank. とは is linked to 神代も聞かず. (くくる tie 四終)

Commentary:

Multiple literary devices—personification of Tatsuta River, metaphor of the tie-dyed river, and the inversion of word order in the poem—enhance the depiction of a vibrant autumn scene. This poem was originally a byōbu-uta, a poem composed to accompany paintings on a folding screen (byōbu).

This is, according to some, a passionate love poem to Nijō-no-Kisaki (Fujiwara-no-Takaiko), the Empress! Her ex-lover Narihira stole her away from the Imperial Palace (truly an event ‘never before heard of’), but she was brought back and his career suffered a setback. The crimson leaves would then represent his undying love for her.

#18.

藤原敏行朝臣

| 住 |

The Sumi Bay |

| 岸 |

shore where waves approach |

| よるさへや |

even at night |

| 夢 |

on the pathway in my dreams |

| 人目 |

you seem to be hiding from people. |

【住の江の】 Sumiyoshi-ku, Osaka.

【岸に寄る波】 Lines 1 and 2 are the jo-kotoba for ‘night.’ (よる approach 四体)

【よるさへや】 よる is a kake-kotoba, meaning ‘approach’ (寄) and ‘night’ (夜); や adds exclamation and forms a kakari-musubi with らむ. (よる approach 四終)

【夢の通ひ路】 One sees a lover in dreams, for only then is there a ‘pathway’ for them to meet. (かよふ pass through 四体)

【人目よくらむ】 らむ “might be (hiding from people).” [(よく avoid 四終) (らむ Conjecture 四体)]

Commentary: This poem was composed from the perspective of a woman at a Poetry Contest held by Empress Hanshi in the Kampyō era (889-898 CE). In the Heian period, if one dreamt of a beloved person frequently, it was thought to mean that one’s love was requited. Women often worried about being deserted and betrayed by a lover or husband. Thus, it is not hard to imagine a situation wherein a woman involved in a secret love pondered what the absence of the man from her dreams suggested about his love interest in real life. This poem conveys the melancholy and frustration of the narrator as she wonders, “Why are you hiding from people, even in my dreams, when there is no chance of being seen by others?” This description leads the reader to associate the constantly changing waves with the emotional changes of a love-stricken heart and to attribute a dreamlike characteristic to the lovers. The Fujiwara family came to dominate the government as Emperors married almost exclusively from this family.

#19.

伊勢

| 難波潟 |

Naniwa Marsh |

| 短 |

short as the reeds’ |

| 節 |

spacing between the nodes – |

| 逢 |

‘Without meeting, this life |

| 過 |

shall pass,’ you said! |

【難波潟】 Near Osaka Bay, it epitomized bleak forlornness.

【短き蘆の】 蘆 a common reed 2 to 6 meters in height. The 1st and 2nd lines are the jo-kotoba for this poem. 短き modifies both 蘆 and 節 in the next phrase. (みじかし short ク体)

【節の間も】 ふし is a kake-kotoba for ‘node’ (節) and ‘lie down’ (臥) – time together, both being short.

【逢はでこの世を】 逢ふ implies intimacy. よ is a kake-kotoba meaning ‘life’ and ‘node’(節) and along with ふし(節) is an en-go of 蘆. [(あふ meet 四未) (で = ず Negative 特用 + つ Perfect 下用)]

【過ぐしてよとや】 や indicates exclamation: “you said (this life) would pass!” [(すぐす pass 四用) (つ Perfect 下用)]

Commentary: This poem captures Lady Ise’s exasperation towards a detached lover, as she asks in her poem, “Is not seeing each other, even though life is as short as the reeds and their nodes, what you were saying?” One might wonder who the man was that had so heartlessly dismissed Lady Ise, as Lady Ise was so charming and loved by sons of regents and men from the Imperial family alike. Nevertheless, the image of short reeds in the dreary tideland characterizes the passion and bitter resentment of Lady Ise, as do the skillful and creative usage of the jo-kotoba, kake-kotoba, and en-go in the poem.

#20.

元良親王

| わびぬれば |

Already distressed |

| 今 |

everything will be the same now |

| 難波 |

in Naniwa; |

| みをつくしても |

even if it kills me |

| 逢 |

I still want to see you. |

【わびぬれば】 わび – ‘grieved’ [(わ ぶ grieve 上用) (ぬ Past ナ已) (ば Resultative)]

【今はた同じ】 はた – ‘again’

【難波なる】 Near Osaka, often referred to in waka as a dreary place. (なり=にある be in ラ体) (cf #19)

【みをつくしても】 みをつくし is a kake-kotoba meaning ‘exhaust oneself’ (身を尽くし) and ‘channel marker’ (澪標) [(つくす exhaust 四 用) (つ Perfect 下用)]

【逢はむとぞ思ふ】 ぞ implies intention and forms a kakari-musubi with おもふ. Elision ‘zomohu’ [(あ ふ meet 四未) (む Conjecture 四終)] (おもふ think 四体)

Commentary: Fujiwara-no-Hōshi was originally a court lady to Emperor Daigo, but her famed beauty later earned ex-emperor Uda’s favor and he took her. Prince Motoyoshi’s love affair with her, now revealed, could be seen as a treacherous act challenging the authority of the Emperor. Despite the danger, Prince Motoyoshi expresses his passion toward Hōshi, even though it might “exhaust” him; i.e., cause his death in this situation. His reference to a channel depth marker might also refer to the depth of his tears, or of his troubles.

#21.

素性法師

| 今来 |

“I am coming right away,” |

| 言 |

you just said; |

| 長月 |

the late autumn |

| 有明 |

waning moon |

| 待 |

has risen as I wait. |

【今来むと】 The speaker of 今来む is a man, though the poem is written from the perspective of the woman who is waiting. [(く come カ未) (む Conjecture 四終)]

【言ひしばかりに】 [(いふ say 四 用)(き Past 特体)]

【長月の】 長月 is when the nights are long in late autumn.

【有明の月を】 有明の月 is a moon still visible at dawn, after the full moon (16th day) of every lunar month.

【待ち出でつるかな】 つる + かな conveys his disappointment and forms a kakari-musubi with まちい でつる. [(まつ wait 四用)(いず emerge 下用)(つ Perfect 下体)]

Commentary: This poem is written from the perspective of a woman who has been waiting for a man all night. At the time when this poem was composed, men and women in relationships had distinct roles; namely, the woman waited patiently at her residence for the man to come. Here, rather than the man, the moon rises to greet her. ばかり has a similar effect: it was only because the man had made a promise that she waited for so long. However, this poem is not merely one of disappointment and sorrow. There is a nonchalance to the poem, as if the man’s absence enhances the poignancy of the moon in the sky, which she would not otherwise have noticed.

#22.

文屋康秀

| 吹 |

Soon after it blows, |

| 秋 |

the autumn plants |

| しをるれば |

wither, so |

| むべ |

I see why the mountain wind |

| あらしというらむ |

is termed a wild storm. |

【吹くからに】 からに ‘right after’ (ふく blow 四終)

【秋の草木の】 The autumn plants.

【しをるれば】 [(しをる wither 下已)(ば “because”)]

【むべ山風を】 むべ ‘I see.’ 山風 is a harbinger of the winter.

【あらしというらむ】 あらし is a kake-kotoba meaning ‘storm’ (嵐) and ‘devastated’ (荒); Combining 山 and 風 to produce 嵐 is an example of acrostic wordplay. [(い ふ say 四終)(らむ Conjecture 四 終)]

Commentary: Influenced by Chinese poets employing acrostic wordplay during the late Six Dynasties period, Japanese poets also started incorporating this into their poems. In the above poem, Yasuhide has depicted the wind (風) coming from the mountain (山) as so wild that it is like a devastating storm (嵐), so 山+ 風=嵐. Other examples include the following poem in Kokin Wakashū by Ki-no-Tomonori: 雪降れば木毎に花ぞ咲きにけるいづれを梅とわきて折らまし ‘Since the snow is falling, flowers are blooming on every tree, so I should distinguish which ones are the plum trees before breaking the tree branches’: 木+毎=梅. Other combinations such as 十+八+公=松 and 八+木=米 are used in 離合詩 (acrostics).

#23.

大江千里

| 月見 |

As I look at the moon |

| 千々 |

countless things |

| 悲 |

make me sad |

| わが |

though not for me alone |

| 秋 |

has the autumn come. |

【月見れば】 見れば indicates fixed conditions. [(みる see 上已)(ば Resultative)]

【千々にものこそ】 こそ adds emphasis and forms a kakari-musubi with 悲しけれ in the following line.

【悲しけれ】 (かなし sad シク已)

【わが身ひとつの】 一人 was changed to ひとつ in this poem to correspond to and contrast with 千々 に in the second line. ‘Not’ is from the next line.

【秋にはあらねど】 ‘Although the autumn has not come for me alone’. Elision ‘aki ni warane do’[(あり be ラ未)(ず Negative 特已)(ど Contradictory)]

Commentary: This poem is based on a verse in the poem ‘Yanzi-lou’ (‘Pavilion of Swallows’) composed by the famous Chinese poet Bai Juyi: 燕子楼の中霜月の夜 秋来たりてただ一人のために長し ‘A frosty moonlit night in the Pavilion of Swallows, the autumn is dragging on for me alone,’ which describes the patient devotion of Director Zhang’s lover, even after he has passed away. Therefore, instead of the poet’s own emotions, #23 is more about the woman’s feelings as depicted in Bai Juyi’s poem. However, ‘Pavilion of Swallows’ only focuses on the sadness of one person, while Chisato’s poem has a certain universality that could apply to anyone. The association of the moon or autumn with sad emotions was widely accepted in Heian literature. The author even works in some Chinese-style parallelism with "moon"-"body" and "thousands"- "one".

#24.

菅家

| このたびは |

This trip |

| 幣 |

even the offering was not brought; |

| 手向山 |

Mount Tamuke - |

| 紅葉 |

brocades of crimson leaves |

| 神 |

left to the whim of the god. |

【このたびは】 たび is a kake-kotoba meaning ‘travel’ (旅) and ‘time’ (度)

【幣も取りあへず】 ぬさ colored cotton strips inscribed with prayers to Hachiman, presented as one embarks on a trip. Elision: nusa mo torya ezu [(とる take 四用)(あふ bear 下未)(ず Negative 特終)]

【手向山】 たむけ is a kake-kotoba meaning the mountain and ‘offering’ (手向)

【紅葉の錦】 The leaves substitute for the brocade to be offered.

【神のまにまに】 まにまに means “at the mercy of...,” so this segment means ‘please accept this offering and grant us safe travel.’

Commentary: Michizane, recently made Minister of the Right, composed this poem when accompanying Retired Emperor Uda to a temple on Mount Tamuke prior to a hunting expedition. As to why the offering had been left behind, one explanation is that by etiquette, Michizane would not have been allowed to present his offering at the same time as the Emperor. Alternatively, perhaps the offering was left behind due to their haste. By presenting the crimson autumn leaves as tribute, the poet portrays a magnificent scene in which the myriad autumn leaves on the mountain—not just the normally pre-made strips of nusa—are offered to the gracious and mighty god. This image glorifies the deity’s power to control the nature and grant the Retired Emperor and his entourage safe travel.

#25.

藤原定方

| 名 |

If the name is accurate - |

| 逢坂山 |

like the Rendezvous Slope |

| さねかづら |

Clinging Vine - |

| 人 |

unknown to others |

| くるよしもがな |

I hope I can get to you. |

【名にし負はば】 ‘If bearing the name’; し adds emphasis. Elision ‘shyo.’ [(おふ bear 四未)(ば “if”)]

【逢坂山の】 逢坂山 is an uta-makura, a mountain checkpoint between Kyoto and Shiga. あふ is also a kake-kotoba meaning a place and ‘meet’ (逢ふ).

【さねかづら】 さね is a kake-kotoba meaning ‘cling’ and ‘sleep together’ (さ寝). The first three lines are the jo-kotoba for くる in the last line.

【人に知られで】 [(しる know 四 未)(る Passive 下未)(で=ずて – ず Negative 特用, つ Perfect 下用)]

【くるよしもがな】くる is a kake-kotoba meaning ‘come’ (来) and ‘spin’(繰) and the en-go for さねか づら. (く/くる come/spin カ/四体)

Commentary:

The double meanings of the many kake-kotoba might make the poem seem puzzling at first, but the double meanings all connect under one theme: romantic attraction to a woman. It is said that this poem was a gift from Sadakata to a woman, given with an actual climbing vine, sanekazura.

Like #22, in which the “storm” owes its name to its devastating power, this poem also demonstrates how names of places and objects were often used in Heian poems to trigger association with ideas and themes, some of which function as uta-makura. The image of the entwined winding vines of the “sleeping together” sanekazura gives the reader mental associations of a romantic encounter and tenacious love.

#26.

貞信公

| 小倉山 |

Mount Ogura – |

| 峰 |

maple leaves on the ridge, |

| 心 |

if having such an inclination, |

| 今 |

now one more time |

| みゆき |

please await an imperial visit. |

【小倉山】 A mountain northwest of Kyoto with spectacular autumn scenery where Fujiwara-no-Teika compiled this collection, the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu.

【峰のもみぢ葉】 autumn

【心あらば】 Elision ‘kokoraraba.’ [(あり be ラ未)(ば “if”)]

【今ひとたびの】 “(Await an imperial visit) one more time.”

【みゆき待たなむ】 みゆき ‘imperial visit.’ なむ expresses a wish or a desire that the leaves await the Emperor. [(まつ wait 四未)(な む Optative)]

Commentary: Retired Emperor Uda was so impressed by the autumn scenery on Mount Ogura that he recommended that his son, Emperor Daigo, visit the mountain. Tadahira agreed to compose this poem as an invitation to Daigo. Like #24, this outing most likely occurred after a hunt, was composed by an attendant of a Retired Emperor, and red maple leaves are mentioned. Furthermore, Tadahira was likely to have been implicated in his older brother Tokihira’s quarrel with Sugawara-no-Michizane (#24). After Michizane’s demotion, Tokihira died, allegedly due to Michizane’s revengeful ghost. Tokihira’s death led to Tadahira’s becoming leader of the Fujiwara clan. Therefore, this poem not only reflects the harmonious interrelations between an Emperor, a Retired Emperor, and a courtier and their appreciation towards the nature, but might also suggest that Teika (redactor of HNIS) was aware of the power struggle involved.

#27.

中納言兼輔

| みかの |

(Across) the plain of Mika |

| わきて |

gushing flows |

| いづみ |

the Izumi River; |

| いつ |

when could I have met you |

| 恋 |

that I am so smitten? |

【みかの原】 Near Kyoto

【わきて流るる】 わき is a kake-kotoba meaning ‘divide’ (分) and ‘gush forth (湧), and is an en-go for いづみ. Hence ‘it flows gushing and dividing.’ [(わく gush/ divide 四 用)(つ Perfect 下用)](ながる flow 下体)

【いづみ川】 いずみ is a kake-kotoba also meaning ‘spring.’ The first three lines are the jo-kotoba for いつ見き, which also echoes いづみ.

【いつ見きとてか】 とて=という; か forms a kakari-musubi with こひ しかららむ in the next line [(みる see 上―用)(き Past 特終)]

【恋しかるらむ】 [(こひし beloved シク体)(らむ Conjecture 四体)]

Commentary: Putting the phrases in their correct orders and the kake-kotoba together, this poem can be translated as “Like the “izumi” River, which flows as it gushes forward and divides the plain of Mika, when (itsu-mi) did we ever see each other that I am so love-struck?” The verses skillfully combine the flowing streams of Mika Plain with a yearning emotion, unfolding innocent first love.

#28.

源宗于朝臣

| 山里 |

The mountain hamlet, |

| 冬 |

winter isolation |

| まさりける |

grows deeper; |

| 人目 |

men and grass |

| かれぬと |

have all withered away. |

【山里は】 山里 often refers to the picturesque mountain villas on the outskirts of the capital.

【冬ぞ寂しさ】 ぞ adds emphasis, implying that “of all seasons, winter is especially lonesome” and forms a kakari-musubi with まさりける.

【まさりける】 [(まさる increase 四 用)(けり Exclam ラ体)]

【人目も草も】 め is a kake-kotoba meaning ‘eye’目 and ‘sprout’ (芽) and serve as an en-go for ‘grass.’

【かれぬと思へば】 かれ is a kake-kotoba meaning ‘separate’ (離) and ‘wither’ (枯)Elision: tomoe [(かる wither/depart 下用)(ぬ Perfect ナ 終)][(おもふ think 四已)(ば ‘because’)]

Commentary:

As winter arrives, the mountain village becomes even lonelier as there are neither visiting guests nor grass. The absence of people and the withered plants also symbolize the natural tendency towards deterioration and death of people and nature, like the final days before death. The model for this poem was written by Fujiwara-no-Okikaze: 秋くれば虫とともにぞなかれぬる人も草葉もかれぬと思へば. However, unlike Okikaze’s poem, which describes a lonely autumn, #28 chooses winter instead to heighten the sense of forlornness created by the absence of people and the withering vegetation. Occult aesthetics and spiritual occurrences in waka poems were best delivered through winter as a medium to a quiescent and monochrome world.

The Minamoto family sprang from Emperor Seiwa (856-877) and established the Kamakura Shogunate in 1185, ending direct Imperial rule.

#29.

凡河内躬恒

| 心 |

By chance |

| 折 |

I would pluck one, were I to try; |

| 初霜 |

since the first frost's |

| 置 |

falling makes indistinguishable |

| 白菊 |

flowers of white chrysanthemum. |

【心あてに】 ‘Guessing’; Elision ‘kokorateni.’

【折らばや折らむ】 や implies doubt and forms a kakari-musubi with を らむ [(をる pluck 四未)(ば “if”)(む Conjecture 四体)]

【初霜の】 The first frost of the year usually occurs during late autumn.

【置きまどはせる】 置き refers to the falling of the frost, indistinguishable from the white chrysanthemum. [(おく place 四 用)(まどはす confuse 四未)(す Causative 特未)(る Passive 下終)]

【白菊の花】 Taigen-dome - using a noun to end a poem was a popular figure of speech to create a lingering image.

Commentary: Chrysanthemums were originally imported from China as medicinal plants and were first written about in Kokin Wakashū. They have become the national emblem of Japan and were adopted as the imperial crest (hence the Japanese imperial dynasty is termed “Chrysanthemum Throne.”) In this poem the hoar frost is described as hardly distinguishable from the white petals of the chrysanthemum. This comparison, mi-tate (見立て), captures the elegant figures of white chrysanthemums through the clear, shiny, and refreshing characteristics of the first cold hoar frost. With the inversion of word order in this poem, “flowers of the white chrysanthemum” is put at the very end of the poem to emphasize its exquisite subject.

#30.

壬生忠岑

| 有明 |

The waning moon |

| つれなく |

appears indifferent; |

| 別 |

since parting, |

| 暁 |

only the dawn, |

| 憂 |

nothing else is as sad. |

【有明の】 有明 refers to the moon still visible in the sky at dawn.

【つれなく見えし】 The moon’s indifference adds to that of the lady from whom the narrator has parted. [(つれなし indifferent ク用)][(みゆ seem 下用)(き Past 特終)]

【別れより】 より ‘since’ or ‘than’

【暁ばかり】 暁 ‘dawn’ and ばかり correlates with なし in the next segment, meaning “there is no...like...”

【憂きものはなし】 うき ‘gloomy’ ‘There is no other moment as gloomy as dawn.’ (うし sad ク 体)(なし not be ク終)

Commentary: When Emperor Go-Toba asked Fujiwara-no-Teika and Ietaka for a distinguished poem from Kokin Wakashū, both recommended this poem. The common interpretation is a saddened man returning home at dawn after parting from his indifferent lover, with an association between the coldness of the lady and the coldness of the waning moon. Dawn refers to the general time a man returns from his lover’s residence. The waning moon is often visible in the eastern sky at daybreak, appearing larger and bleaker since it is low on the horizon. However, Teika commented that “it is only the waning moon that appears to be cold, not the lady.” Therefore, Teika sees the cold moon as a contrast to the passionate night the man has spent at the lady’s residence instead of a comparison. Whether it is a contrast or a similarity between nature and the human world, this famous poem provides a vivid night scene and leaves the reader room to interpret the situation.

#31.

坂上是則

| 朝 |

Dawning twilight – |

| 有明 |

with the waning moon |

| みるまでに |

one might think |

| 吉野 |

on the village of Yoshino |

| 降 |

is falling – white snow! |

【朝ぼらけ】 When light first appears in the sky before sunrise.

【有明の月と】 The moon still visible in the sky at dawn.

【みるまでに】 (みる think 上―終)

【吉野の里に】 Yoshino – mountain village near Nara known for its cherry blossoms.

【降れる白雪】 Ending the poem with a noun is taigen-dome, intended to create a lingering imagery. The comparison of moonlight to snow is a mi-tate. [(ふる fall 下未)(る Natural 下終)]

Commentary: Upon first seeing a moonlit yard during the winter, one might mistake it for a snow-covered scene, as in Chinese poet Li Bai’s famous verse, “牀前月光を看る 疑うらくは是地上の霜かと (The bright moonlight before my bed, could it be hoar frost on the floor?)” This poem was composed in the winter of 908 when Korenori was proceeding to his new appointment in Yamato Province. It is said that he composed this poem after waking up in a lodging near the mountains in Yoshino at dawn and was impressed by the snowy scene outside. Yoshino is a place where many Emperors built imperial villas, so to residents in the capital Yoshino is a detached village. Therefore, rather than with loneliness, a snow-covered Yoshino village is more strongly associated with time immemorial and peaceful quiet. In addition, in the poem Yoshino is adorned by a blanket of moonlight as if the sleeping village would remain forever in such tranquility.

#32.

春道列樹

| 山川 |

On a mountain stream |

| 風 |

a wind-built |

| しがらみは |

dam |

| 流 |

impedes the flow |

| 紅葉 |

made of maple leaves. |

【山川に】 On a mountain stream

【風のかけたる】 [(かく build 下用)(たり Perfect ラ体)]

【しがらみは】 しがらみ(柵), is a barrier or dam made of wood or bamboo built across a river in order to regulate the water flow. しが is a kake-kotoba also meaning Shiga Temple.

【流れもあへぬ】 The maple leaves block the stream. [(あふ allow/bear 下未)(ず Negative 特体)]

【紅葉なりけり】 けり an exclamation, suggests that the poet was deeply moved by the view of the maple leaves. Mi-tate of maple leaves to a dam. [(なり be ナリ 用)(けり Exclam ラ終)]

Commentary: It was noted in Kokin Wakashū that this poem was composed at the Yamanaka checkpoint on Mount Shiga, on the mountain route starting from Kyoto and coming out at the village of Shiga (present-day Ōtsu City, Shiga Prefecture). This was the route taken by people paying homage at the Sūfuku Temple in Shiga. As a place with beautiful cherry blossoms falling like snowflakes every spring, Shiga is also famous as an uta-makura. The poet also implies the resistance of nature to the will of man. Inspired by this poem, the main compiler of Kokin Wakashu, Ki-no-Tsurayuki, composed the following poem: 年ごとにもみじ葉流す竜田川みなとや秋の泊まりなるらむ (Kokin Wakashū Autumn 2-311). ‘Every year maple leaves flow along the Tatsuta River, the estuary where the maple leaves blanket the stream is a harbor for autumn.’

#33.

紀友則

| 久方 |

On a bright |

| 光 |

sunlit, calm |

| 春 |

spring day – |

| しづ |

with hearts untranquil |

| 花 |

the cherry blossoms scatter. |

【久方の】 A makura-kotoba often used for the sun, Emperor, etc, here associated with 光 in the second line, also carrying a nuance of tranquility.

【光のどけき】 (のどけし calm ク 体)

【春の日に】 On a spring day

【しづ心なく】 しづ心 calm. ‘Heart’ here refers to the heart of a flower, since the poet is personifying the flowers in this poem.

【花の散るらむ】 花 here refers to cherry blossoms. [(ちる scatter 四 終)(らむ Conjecture 四終)]

Commentary: The headnote of this poem in the Kokinshū says it is composed “on the falling of the cherry blossoms.” The restlessness of the cherry blossoms contrasts with the peacefulness of a sunny day in spring. This could also be a contrast between eternity and an instant, or might also imply that even eternity (imperial power) is constantly changing. Even though falling petals suggest decay and sadness, the falling blossoms are described as a somewhat incongruent but beautiful scene on a peaceful day in spring. Also, the repetition of “ha” column syllables (久方, 光, 春の日,花) and the four の’s create unique pauses in the rhythm that the reader can visualize as a sharp transition from the peaceful scene of a sunny day in spring to the scattering cherry blossoms. Perhaps it is not the cherry blossoms that lack placid hearts, but the people watching the falling cherry blossoms, or are the people watching the scattering cherry blossoms concerned for the continued tranquility of the imperial reign?

#34.

藤原興風

| 誰 |

Whom then |

| 知 |

Shall I befriend? |

| 高砂 |

The Takasago |

| 松 |

pine from old-times |

| 友 |

is not even a friend. |

【誰をかも】 Whom then? も adds emphasis; か forms a kakari-musubi with せむ in the next line.

【知る人にせむ】 知る人 here means “people who know me well.” (しる know 四体)[(す make サ未)(む Conjecture 四終)]

【高砂の】 An uta-makura. Takasago in Hyōgo Prefecture is famous for its pine trees by the shore.

【松も昔の】 Long-lived pine trees.

【友ならなくに】 “Though (the pine tree) is not a friend (from the old days).” [(なり be ナリ未)(ず Negative 特終)]

Commentary: In Zeami’s Noh play Takasago, an old couple appears from the mist on Takasago Bay in front of a Shinto priest. They are talking happily and sweeping up the needles under the renowned Takasago Pines which, along with the famed Suminoe Pine of distant Sumiyoshi, are called aioi-no-matsu, or “Paired Pines.” The old couple is the incarnation of the Paired Pines. They use a broom to sweep away trouble and a rake to gather good fortune. The couple and the pines in the legend of Takasago have come to symbolize the happiness of family life and longevity. The basic sense of this poem is that as the narrator’s friends have all passed away, even the pines cannot provide companionship for the narrator despite their longevity. This is a poem that ironically laments longevity as close friends pass away.

#35.

紀貫之

| 人 |

People, well, |

| 心 |

I do not know their hearts; |

| ふるさとは |

but this old village – |

| 花 |

the flowers like in the old days, |

| 香 |

are fragrant still. |

【人はいさ】 いさ indicates a negation, here means “(not) well”

【心も知らず】 も adds emphasis. [(しる know 四未)(ず Neg 特終)]

【ふるさとは】 ふるさと a long-familiar place. は shows distinction.

【花ぞ昔の】 The flowers in contrast to the hearts of the people. ぞ adds emphasis and forms a kakari-musubi with にほひける.

【香に匂ひける】 匂ひ fragrant, bright, colorful. [(にほふ be fragrant 四用)(けり Past ラ体)]

Commentary: This poem is preceded by a headnote in the Kokin Wakashū: “There was a house where the poet stayed each time he made a pilgrimage to Hatsuse (Nara Prefecture), but had not been able to visit for some years. When the poet finally visited again, the house owner said ‘As you can see, your lodging is where it always was in the past,’ whereupon the poet broke off a branch from the plum tree planted there and composed this poem.” The house owner’s remark can be interpreted as a slightly annoyed comment about the poet’s lack of visit, though his lodging has always been there. In this context, the poet seems to mean: “I cannot fathom people’s hearts and I do not know whether you feel the same way towards me as in the past, but in this familiar village the plum blossom is as fragrant as ever.” As the flow of time gradually obscures one’s feelings, the reunion of two old friends or lovers, mixed with the spring sentiment and fragrant plum blossom scent, awakens the past and lingers in the simplicity of the nature.

#36.

清原深養父

| 夏 |

This summer night |

| まだ |

still just getting dark |

| 明 |

yet it's already dawning! |

| 雲 |

So where in the clouds is |

| 月 |

the moon dwelling? |

【夏の夜は】 は emphasizes the subject – this summer night.

【まだ宵ながら】 After sunset and before dark.

【明けぬるを】 It has dawned. を means “because” and connects with the next line. [(あけ dawn 下用)(ぬ Perfect ナ体)]

【雲のいづこに】 いづこ where.

【月やどるらむ】 らむ indicates a conjecture, conveying the speculation that, “the moon is probably dwelling behind some clouds.” [(やどる 四終)(らむ Conjecture 四終)]

Commentary: This poem of a mere five lines consists of a number of cultural assumptions and insights into nature. The short duration of a summer night is the basis of the poet’s conjecture and the personification of the moon as someone “dwelling (やどる) among the clouds.” Another belief is that the moon “resides” in the western mountains, since it is always seen setting behind the mountains and hills in the west. We could interpret this poem as follows: “This summer night is so brief that the day has dawned already while it still seems like evening, leaving too little time for the moon to make it back to its western mountain home. Where in the clouds might the moon be dwelling then?” The poet has cleverly incorporated personification and his personal emotion to create a delightful image of the moon hurrying back home but needing to lodge behind the clouds momentarily as the sun rises, as well as the poet himself looking for the moon as if he wants to admire it once more before it can hide again.

#37.

文屋朝康

| 白露 |

In the glistening dew |

| 風 |

blown by the heedless wind |

| 秋 |

this autumn field – |

| つらぬきとめぬ |

unstrung |

| 玉 |

pearls scatter around. |

【白露に】 しら emphasizes the cleanness and purity of an object.

【風の吹きしく】 [(ふく blow 四用)(しく do repeatedly 四体)]

【秋の野は】 は emphasizes the subject – the field in autumn.

【つらぬきとめぬ】 [(つらぬく string 四用)(とむ keep in place 下未)(ず Negative 特体)]

【玉ぞ散りける】 玉 ball, sphere, pearl, jewel, etc. Mi-tate likens the scattered dew blown by the incessant wind to pearls splattering from a broken string. ぞ adds emphasis and forms a kakari-musubi with ける which expresses excitement. [(ちる scatter 四用)(けり Exclam ラ体)]

Commentary: Strong winds are commonplace on autumn grasslands in Japan. As the wind blows incessantly, the shining dew or rain drops fall and scatter like unstrung pearls. Moreover, onomatopoeia of “し” in “白露に風の吹きしく” and of た sounds in “つらぬきとめぬ たまぞちりける” mimics the sound of the rain and wind, further bestowing upon the reader the sensation of the refreshing autumn air. Shining dew is also compared to pearls in the Kokin Wakashū and the famous Tale of Genji. Here are two examples: 浅緑糸よりか けて白露を玉にもぬける春の柳 (Henjō Kokin Wakashū Spring Volume 1-27) ‘twisting the light green thread that strung the shining dew drops together like pearls, this spring willow tree.’ Another of Funya-no-Asayasu’s poems, 秋の野に置く白露は玉なれやつらぬきかくる蜘蛛の糸筋 (Kokin Wakashū Autumn Volume 1-225), ‘Are the dew drops dotting the autumn fields not pearls? Weaving together those pearls on the leaves is the spider silk.’

#38.

右近

| 忘 |

Forgotten, |

| 身 |

I do not think of myself; |

| 誓 |

you made a promise – |

| 人 |

that life of yours |

| 惜 |

is what I pity. |

【忘らるる】 [(わする forget 四 未)(る Passive 下体)]

【身をば思はず】 身 ‘myself.’ は becomes ば after を. [(おもふ think 四未)(ず Negative 特終)]

【誓ひてし】 (You) having vowed. [(ちかふ swear 四用)(つ Perfect 下 用)(き Past 特体)]

【人の命の】 人の your

【惜しくもあるかな】 惜しく ‘precious’ conveys the narrator’s concern and sadness towards the man who will be punished by the gods for breaking his vow. かな adds emotion and forms a kakari-musubi with ある. Elision ‘maru.’ (をし pity シク用)(あり be ラ体)

Commentary: This poem is followed by this introduction in section 84 of Tales of Yamato: “This same lady (Ukon), after a certain gentleman had sworn in every possible way to the gods that he would never forget her, but still did, composed this poem and sent it to him.” Knowing this context, one could naturally see the poem as highly sarcastic towards the hypocrisy of the lover. The second half of the poem hints that Ukon’s neglectful lover will die now that he has abandoned her. The words appear threatening, yet they are composed in such a mild and subtle way that they fully demonstrate the narrator’s sorrow and sadness. It is speculated from evidence in Tales of Yamato that Ukon sent this poem to Fujiwara-no-Atsutada (#43). Coincidentally, Atsutada died at the early age of 38.

#39.

参議等

| 浅茅生 |

The sparse blady grass, |

| 小野 |

plain with its short bamboos, |

| 忍 |

though I have concealed it, |

| あまりてなどか |

it overwhelms me – why |

| 人 |

do I love her so? |

【浅茅生の】 A makura-kotoba for the field in the next line.

【小野の篠原】 しの(はら) is the jo-kotoba for 忍ぶ in the next line due to the sound repetition しの(ぶれ).

【忍ぶれど】 しのぶれ is a kake-kotoba meaning ‘conceal/endure’ (忍ぶ) and ‘love’ (偲ぶ). [(しのぶ conceal 上已)(ど “although”)]

【あまりてなどか】 あまりて – overwhelming; など + か – why; か also forms a kakari-musubi with こ ひしき below [(あまる exceed 四 用)(つ Perfect 下用)]

【人の恋しき】 恋しき – beloved. (こひし beloved シク体)

Commentary: This poem alludes (honka-dori) to 浅茅生の小野の篠原しのぶとも人知るらめやいふ人なしに (Kokin Wakashū Love Volume 1-505), ‘The sparse blady grass, short bamboos of the plain – this hidden emotion, shall I let that person know of it? No I shall not, as there is no one to deliver it.” In contrast, lines 3-5 of #39 can be paraphrased as “I have concealed it, yet it overwhelms me – why do I love her so?” The jo-kotoba not only serves as a part of the wordplay, but also describes a desolate yet touching scene that contrasts with the narrator’s overwhelming affection and hints at the fruitless hidden love. The tall bamboos in a field of sparse blady grass reflect the narrator’s excessive affection. These expressions depict the confusion and towering passion one experiences in a secret love.

#40.

平兼盛

| 忍 |

Though I try to conceal it, |

| 色 |

in my countenance shows |

| わが |

my love; |

| 物 |

‘Are you thinking of something?’ |

| 人 |

people finally ask. |

【忍ぶれど】 [(しのぶ conceal/ endure 上已)(ど “although”)]

【色に出でにけり】 色 – face. けり adds the fear of discovery. Elision: ‘ironidenikeri’ [(いづ emerge 下 用)(ぬ Perfect ナ用)(けり Exclamation ラ終)]

【わが恋は】 My love.

【物や思ふと】 物 a vague subject. 物思ふ suggests “thinking about love and suffering from the thoughts.” や implies a question and serves as a kakari-musubi with おも ふ. (おもふ think 四体)

【人の問ふまで】 問ふ ‘ask,’ まで ‘until,’ ‘finally’ (とふ ask 四終)

Commentary: This poem and #41 are presented together in the beginning of Shūishū, an imperial anthology of Japanese waka, with the headnote “From a poetry contest of the Tenryaku Era,” referring to the Palace Poetry Contest in 960. #40 and #41 were the two finalists on the theme “secret love,” but the judge, Fujiwara-no-Saneyori, unable to decide on a winner, appealed to Emperor Murakami, who hummed this poem and decided the contest. Although in the modern sense, the narrator’s concern with people noticing his hidden emotions may appear to be innocent and exaggerated, this poem was composed during a time when societal reputation was highly regarded. There were even situations in which one would prefer death to revelation of a secret love (#89). Despite the fact that one was allowed to have his or her own choice in love relationships, this poem accurately depicts the passion as well as frustration of a secret love with someone of whom society might not approve. The Taira sprang from Emperor Kanmu (781-806) and fought the Minamoto for dominance in 1185.

#41.

壬生忠見

| 恋 |

‘He is in love,’ they say; |

| わが |

my reputation is already |

| 立 |

determined – |

| 人知 |

I have tried to keep it quiet, |

| 思 |

this affair has only just begun. |

【恋すてふ】 (す do サ終)(てふ=と いふ)

【わが名はまだき】 まだき already.

【立ちにけり】 As when one is found out. [(たつ stand 四用)(ぬ Past ナ 用)(けり Exclam ラ終)]

【人知れずこそ】 こそ forms a kakari-musubi with omohisomeshi [(しる know 下未)(ず Negative 特 終)]

【思ひそめしか】 しか ‘only just’ ‘I have only just begun to think of her.’ [(おもふ think 四用)(そむ begin 下 用)(き Past 特已)]

Commentary: 思ひ (“to think”) can refer to both 知れず (“No one knows”) and to そめ (“I just began to think about her”). The most common interpretation is: “The rumor of me being in love has already spread far and wide, even though I have only just begun to love her secretly so that she is unknown to others.” This was the poem that lost to #40 in the Palace Poetry Contest in 960, but it still gained great praise. In the Shasekishū, a collection of parables written during the Kamakura period, the poet Tadami was depicted as dying of depression and anorexia after losing the contest. Although the story is fictional and Tadami continued writing poetry, results of a poetry contest, such as the one mentioned here, were of great importance to poets at that time. #40 might have won the contest because of Emperor Murakami’s personal preference, but this poem has a more appealing tone of calm. One often has delicate and perplexed emotions at the beginning of an affair. This poem honestly depicts the consternation of being discovered.

#42.

清原元輔

| 契 |

We swore (to love each other) didn’t we? |

| かたみに |

while both our sleeves |

| しぼりつつ | we wrung continually, |

| 末 |

“Until the top of Matsuyama |

| 波越 |

is covered by waves,” as they say. |

【契りきな】 な expects an affirmative response. [(ちぎる swear 四用)(き Past 特終)]

【かたみに袖を】 かたみに mutually.

【しぼりつつ】 Sleeves wet from wiping away tear drops [(しぼる wring 四用)(つつ Continuation)]

【末の松山】 Uta-makura for a mountain in Miyagi unreachable bythe sea.

【波越さじとは】 Waves can never overcome Matsuyama (Ehime Prefecture). The 2nd to 5th lines modify the 1st line. [(こす cross 四 未)(じ Negative Conjecture)]

Commentary: This alludes to an anonymous poem: 君をおきてあだし心をわ が持たば末の松山波も越えなむ (Kokin Wakashū The Azuma Poems 1093). ‘If I ever have the heart to abandon you, may waves engulf Mount Suenomatsu.’ The headnote preceding this poem in Goshūi Wakashū says, “For the person whose lover has changed her mind.” な is like ね in modern Japanese as an invitation for the listener to respond and possesses an incredibly pitiful and despairing voice as if the narrator were begging and weeping. It is interesting to note that though both #42 and #38 describe one’s desolation after being abandoned, #42 is not nearly as caustic and bitter as #38, suggesting that the narrator is feeling more regretful about his lingering affection, than angry and spiteful towards the past lover’s changed feelings.

#43.

権中納言敦忠

| 逢 |

Having seen you, |

| のちの |

my feelings afterwards – |

| くらぶれば | if I compare them to |

| 昔 |

those in the past – |

| 思 |

I have never loved before. |

【逢ひ見ての】 逢ふ and 見る describe a lovers’ rendezvous. [(あ ふ meet 四用)(みる see 上―用)(つ Perfect 下用)]

【のちの心に】 のち after (the tryst).

【くらぶれば】 [(くらぶ compare 下 已)(ば “because”)]

【昔はものを】 もの romantic thoughts.

【思はざりけり】 The narrator realizes that his feelings before the rendezvous were nothing in comparison to now. [(おもふ think of/love 四未)(ざる Negative 特 用)(けり Past ラ終)]

Commentary: This poem was preceded by the headnote “Sent the next morning, after he had started visiting the woman.” It seems to be a poem by a man who feels that his previous love affairs pale in comparison with his current love, though some interpret this poem as one in which a man expresses doubts about their love, or some factor preventing the two lovers from meeting again. Another possibility is that the romantic liaison might have been opposed by either party’s family, so the agonizing frustration the narrator experiences now is much more intense and complicated than before the liaison.

#44.

中納言朝忠

| 逢 |

Meeting, (it had been better) |

| 絶 |

if (we had) not (met) at all, |

| なかなかに | on the other hand, |

| 人 |

her (indifference) and my (fate) |

| 恨 |

would not be cause for resentment. |

【逢ふことの】 逢ふ rendezvous. (あ ふ meet 四終)

【絶えてしなくは】 絶えて ‘at all,’ also a kake-kotoba meaning ‘cease’ (絶). し emphatic. なくは and まし below indicate ‘if not ...then.’ – a counterfactual supposition. [(たゆ end 下用)(つ Perfect 下用)]

【なかなかに】 ‘on the contrary’

【人をも身をも】 も ‘both...and’

【恨みざらまし】 Contrary-to-fact. [(うらむ resent 上未)(ざる Neg 特 未)(まし Conj 特終)]

Commentary: The classification of this poem at the time of the poetry contest was “early love before a first meeting.” Later it was reclassified under “lovers that cannot meet again.” The highlight of this poem is the usage of a counter- factual supposition in depicting the narrator’s profound frustration and sadness in a way that is straightforward and easily understood. Under Teika’s interpretation, this poem can be paraphrased as “If we had never met at all, I would not be so resentful towards her indifference and my sorrowful fate.” The reason why the lovers cannot meet again is unclear. However, from the narrator’s resentment towards the woman, it is likely that the narrator is troubled by coldness and neglect from the one he loves. Whether it be that the woman has found a new love, or that she is purposely playing hard to get, this poem skillfully portrays the narrator’s delicate emotional state when his love is not fulfilled. It might be due to its focus on a regretful love, as in #43, that these two poems were placed next to each other.

#45.

謙徳公

| あはれとも | “How sad,” |

| いふべき |

she would likely say, |

| 思 |

if I crossed her mind; |

| 身 |

dying for love in vain |

| なりぬべきかな | seems to be my fate. |

【あはれとも】 あはれ ‘pitiful.’

【いふべき人は】 [(いふ say 四 終)(べし Conjecture ク体)]

【思ほえで】 [(おもほゆ recall 下 未)(で=ずて:ず Negative 特用, つ Perfect 下用)]

【身のいたづらに】 ‘to die in vain.’

【なりぬべきかな】 end up (dying in vain). [(なり be ラ用)(ぬ Perfect ナ 終)(べし Conjecture ク体)]

Commentary: According to the headnote in Shuishū, this poem was composed for a woman who, despite having formed a social intercourse with the narrator, has not replied to the narrator’s amorous entreaties and has not seen him again. Therefore, this poem portrays the desperation and loneliness of a man who has so suffered from his love that he would rather die, yet doing so would probably not even be noticed by the woman. Additionally, the first three lines could also be interpreted as meaning that no one else would sympathize with or understand the narrator after knowing that his romantic pursuit has been unbearably futile. Born into a family of powerful politicians, Fujiwara-no-Koremasa possessed not only proficient scholastic ability, but also good looks. Therefore, it is not surprising that few people would believe that Koremasa encountered a failed love affair.

#46.

曾禰好忠

| 由良 |

The estuary of Yura |

| 渡 |

a boatman flowing across |

| かぢを |

without an oar |

| 行 |

going he knows not where |

| 恋 |

the road of love. |

【由良の門を】 North of Kyoto, where two currents meet with turbulent tides.

【渡る舟人】 舟人 ‘boatman.’ (わた る cross 四体)

【かぢを絶え】 かぢ ‘paddles’ Lines 1-3 are the jo-kotoba for this poem. (たゆ end 下用)

【行くへも知らぬ】 Applies to a boat in the estuary and a person on the pathway of love. (ゆく go 四終) [(しる know 四未)(ず Negative 特 体)]

【恋の道かな】 道 ‘the way’ of love. Estuary, flow, boatman, oar, direction, and way are en-go. かな conveys an exclamation. Taigen-dome

Commentary: The 4th line not only expresses the emotion of the boatman who has lost his direction, but also conveys the concerns and worries of a man who is lost in love – they both share unease towards their hindered, wayward paths. The description of a boatman without a paddle in the estuary brings the intangible emotions surrounding love forcefully to the reader. The only point of contention in this poem is the 3rd line. Most commentators believe that かぢ refers to oar- like wooden tools and を is an object marker, so かぢを絶え means “having lost the oar.” Other commentators, possibly including Fujiwara-no-Teika, interpret かぢを as the noun which means “oar cord,” and under this interpretation かぢを絶え means “the oar cord is severed,” which yields the same result.

#47.

恵慶法師

| 八重葎 |

Tangled catchweed |

| 茂 |

residence rampant with weeds |

| さびしきに | lonely |

| 人 |

I see no one |

| 秋 |

autumn has arrived. |

【八重葎】 やへ ‘overlapping (vines),’むぐら ‘trailing plant,’ a metaphor for a desolate cottage.

【茂れる宿の】 (しげる grow 下体)

【さびしきに】 (さびし lonely シク 体)

【人こそ見えね】 こそ forms a kakari-musubi with みえね [(みゆ see 下未)(ず Negative 特已)]

【秋は来にけり】 けり a sudden realization. [(く come カ用)(ぬ Past ナ用)(けり Exclam ラ終)]

Commentary: The source of this poem, Shūi Wakashū, contains a foreword to this poem that says “At Kawara-in, people discuss the arrival of autumn at the desolate residence.” Kawara-in had been the birthplace of many works by great poets such as Ariwara-no-Narihira (#17). But after the death of Tōru, rumors about his haunting spirit and the flooding of the Kamogawa River led to Kawara-in being deserted. However, during Egyo Hoshi’s time, poets of refined tastes who cherished the residence gathered there once again to continue the production of poems. This group of poets consisted mostly of middle- or lower- class men, but who all shared profound appreciation and affection towards Kawara-in, though now dilapidated and derelict.

#48.

源重之

| 風 |

In the fierce wind, |

| 岩打 |

like a wave battering the rocks, |

| おのれのみ | only I |

| くだけて |

am shattered – |

| 思 |

time for troubling thoughts. |

【風をいたみ】 いたし ‘extreme’ ‘を + み’ indicates a reason. Elision ‘kazyo.’

【岩打つ波の】 Lines 1-2 are the jō- kotoba of くだけて (うつ hit 四体)

【おのれのみ】 のみ ‘only’

【くだけて物を】 [(くだく break 下 用)(つ Perfect 下用)]

【思ふころかな】 ころ ‘time (for thinking)’ か adds emphasis and forms a kakari-musubi with おもふ. (おもふ think 四体)

Commentary: The waves shatter into water drops against the rock, yet the rock remains motionless, as if nothing has occurred. This scene also serves as a metaphor for the narrator’s romantic feelings crashing uselessly into pieces on the unmovable and indifferent woman being pursued. So the first two lines (jo-kotoba) not only describe the waves beating on the rock, but also imply her neglect of the narrator. There is also assonance of the sound “mi,” in いたみ, な み, and のみ. It was trendy in poetry at the time to use the phrase “くだけて物 を思ふ (being shattered, a time to think)” to describe the intensity of one’s troubling thoughts. For example, Sone-no-Yoshitada (#46) composed the following poem: 山賤のはてに刈り干す麦の穂のくだけて物を思ふころか な (Sotanshū 135). It means “Just as the farmer cuts down the last wheat stem and mills it into powder, it shatters me, my thoughts.” Waves shattered by the unmovable rock here and the wheat stem smashed into powder in Yoshitada’s poem are both vivid metaphors of the narrator’s desperation and hurt feelings.

Kuniyoshi for #48

#49.

大中臣能宣朝臣

| 御垣守 |

Imperial court guard |

| 衛士 |

sentinels’ watch-fire |

| 夜 |

burning through the night, |

| 昼 |

morning always puts it out – |

| 物 |

thoughts of love. |

【御垣守】 Imperial gate guards

【衛士のたく火の】 衛士 ‘guards’ Lines 1 and 2 are the jō-kotoba for lines 3 and 4.(たく set (fire) 四体)

【夜は燃え】 (もゆ burn 下用)

【昼は消えつつ】 The 3rd and 4th lines convey the repetitive occurrence of the watch fire burning at night and being extinguished by day. The fire also symbolizes the narrator’s love. [(きゆ extinguish 下 用 )(つつ Continuative)]/p>

【物をこそ思へ】 物を思ふ means “to be lost in thought because of love.” こそ gives emphasis and forms a kakari-musubi with おもへ. Elision: monowokosomohe (おもふ think 四已)

Commentary: ‘Like the watch fire (hi) set by guards of the imperial court, which burns all night and is extinguished during the day, my thoughts of love (omohi) burn up my heart at night and leave me alone through the day.’ The jo-kotoba here (the guards’ watch fire) describes a natural scene, while the last line conveys the narrator’s emotions. The 3rd and 4th lines serve as a link both to the description of the guard’s fire and to the narrator’s emotions. Night is when lovers meet, so, just like the watch fire, love blazes at night and dies out in the morning. In Kyoto, before streetlights, the solitary burning fire lighting up its dark surroundings created a unique poetic atmosphere and has come to symbolize the burning passion of lovers.

#50.

藤原義孝

| 君 |

For your sake, |

| 惜 |

my hitherto uncherished |

| 命 |

life, |

| 長 |

that it might last longer |

| 思 |

I now wish. |

【君がため】 が means の.

【惜しからざりし】 This line implies that in the past, the narrator “would not have cherished (his life).” [(を し pity ク未)(ざる Negative 特 用)(き Past 特体)]

【命さへ】 ‘Even my life.’

【長くもがなと】 もがな expresses the wish to live longer now because of his love. (ながし long ク用)

【思ひけるかな】 かな expresses the narrator’s excited realization of his change of heart. か adds emphasis and creates a kakari-musubi with お もひける [(おもふ think 四用)(け り Exclam ラ体)]

Commentary: Putting all segments of this poem in their logical order, it translates into: “I did not chersih even my life in the past, but now, for the sake of seeing you, I hope it may last longer.” Like #49, this poem expresses the narrator’s passionate love. The headnote preceding this poem in the Goshūi Washū reads, “composed after returning from the lady’s quarters.” Therefore, this poem is interpreted as a “morning-after” poem, composed by a man as he returns home from his first overnight stay at a woman’s residence after an extensive pursuit. In other words, in the past, the narrator was willing to risk his life for love. Yet after a night with this lady, he craves a longer life. This poem depicts the drastic change in the narrator’s attitude towards life, as he begins to enjoy life and love.

#51.

藤原実方朝臣

| かくとだに | Even (loving you) in this way |

| えやはいぶきの | I could not tell you, (like) Ibuki’s |

| さしも |

moxa plant, |

| さしも |

how unaware you are |

| 燃 |

of my burning thoughts. |

【かくとだに】 かく thus; だに even.

【えやはいぶきの】 えやは as if; い ぶき is a kake-kotoba meaning the mountain, ‘breath’ (伊吹) and ‘how should I tell’ (言), and uta-makura for Mt. Ibuki (伊吹山 Gifu Pref), known for its mugwort. [(う get 下 体)(やは Irony)]

【さしも草】 mugwort used in moxibustion

【さしも知らじな】 さしも ‘how, to what extent,’ echoes さしも‘moxa plant.’ な is an interjectory particle. [(しる四未)(じ Negative Conj)]

【燃ゆる思ひを】 ひ in 思ひ is also a kake-kotoba for ‘fire’ (火). さしも 草, 燃ゆる and ひ are all en-gos.

Commentary: The poet employs many poetic literary devices to skillfully convey his love in this poem. The kake-kotobas in the poem could be interpreted as follows: “How should I describe to you (いぶき) that I love you so, and how unaware you are. Like Mount Ibuki (いぶき)’s moxa grass, my thoughts are burning.” The headnote of this poem in its source, Goshūi Wakashū, says, “Composed right after (the poet) started seeing her,” so it is likely that the poet sent this poem as a part of the first letter to the woman he was passionately in love with. Even though they are rarely heard of today, Japanese mugworts were commonly used by people, including ladies, of the Heian period during moxibustion treatments.

#52.

藤原道信朝臣

| 明 |

Though day has dawned, |

| 暮 |

darkness will come again; |

| 知 |

though I know it, |

| なほ |

still, how odious |

| あさぼらけかな | is daybreak! |

【明けぬれば】 [(あく dawn 下 用)(ぬ Perfect ナ已)(ば Resultative)]

【暮るるものとは】 (くる darken 下 体)

【知りながら】 [(しる know 四 用)(ながら “although”)]

【なほ恨めしき】 なほ still (うらめ し hateful シク体)

【あさぼらけかな】 あさぼらけ refers to “daybreak,” in poems; it is the time when a man leaves a lady’s chambers after spending a night together. かな conveys an exclamation and forms a kakari-musubi with うらめしき. Taigen- dome

Commentary: The headnote to this poem in the Goshūi Wakashū reads “sent to a woman after returning from her chambers on a snowy day.” Therefore, this poem is interpreted as a “morning-after” poem, composed by a man as he returns home from an overnight stay at a woman’s residence. At first glance, this poem might appear to be describing a saddening experience, but a closer examination reveals the narrator’s strong wish to stay with the lady and his reproachful feeling towards the start of a day, even though he understands that a night never occurs without daybreak. Reason, which the narrator understands, conflicts with his honest emotion towards separating from his lover during the day. Such contradiction was praised as a refined style of poems, as it portrays the ideal image of a man in love, who unconditionally sacrifices himself in the name of love, even though he knows that certain things he wishes for are unreasonable.

#53.

右大将道綱母

| 嘆き |

I sigh and sigh |

| ひとり |

the night sleeping alone |

| あくる |

the time until dawn; |

| いかに |

just how long |

| ものとかは |

a thing that is, do you even know? |

【嘆きつつ】 [(なげく sigh 四用)(つ つ Continuation)]

【ひとり寝る夜の】 Heian married couples practiced duolocal marriage (通い婚) – the man commuted to his wife’s residence at night. Here the narrator was not visited by her husband. (ぬ sleep 下体)